Why didn’t Matthew just name the game?

Well he is a sensitive guy and I know he’s aware that

for some people the name of the game is an issue of great significance,

one that is capable of creating a degree of debate and sometimes

rancour. If that was his reason then he needn’t have been so

thoughtful, I’m happy with the term soccer, something which puts me at

odds with many Australian supporters of the game.

In recent years many proponents of soccer in Australia have

begun to call the game football. In 2004, Football Federation Australia

(FFA) replaced Soccer Australia as a part of sweeping reforms to the

game’s management, effectively ‘taking back’ the name football – a move

that received a deal of support in the soccer community but one which

generated a great degree of opposition and disagreement from supporters

of Australian rules football and the Rugby codes.

This is understandable. ‘Football’ is a very powerful term.

Whenever it is used it also represents an incidental assertion of the

hegemony of the game it is describing. Australian rules proponent,

Martin Flanagan believes the

football naming-rights argument is a small matter of

large consequence. Politics is largely decided by headlines that

transfer the meaning of a mere handful of words. In sport, in this part

of the world, one of those words is football. Whoever owns that word

to some extent owns the future.

Prior to 2004, in most of Victoria, Tasmania,

South Australia and Western Australia ‘football’ denoted Australian

rules; in Queensland and New South Wales it usually meant Rugby League.

And while generally these conventions still hold they have been

destabilised by the re-naming of soccer.

Significantly, the intense

branding of terms like NRL (National Rugby League) and AFL

(Australian Football League, the peak Australian rules body) has allowed

soccer some space and leverage in adopting the term football. But we

need to be careful to draw a cultural distinction between what the PR

agents denote and that which the general public connotes.

This new policy of soccer ‘taking back’ the name of football is based on a few fallacies:

-

That the use of the term soccer was forced upon the game.

This is only partly true. In Australia the name soccer was adopted

to in order to both domesticate the game and internationalise

its image. The term British Association football was seen as tying the

game too tightly to British roots. The preferred option,

Association football, was unavailable, already taken by the

second-string Australia rules competition in Victoria. Soccer was

the only term available that referenced Association football

unambiguously.

-

Soccer is an American abomination.

This is not true. The term was invented in English public schools

– though not necessarily without a pejorative aspect. Pet oxford name

-

Soccer is a diminutive that belittles the game. This is a matter of emphasis and manner of articulation. Any diminution is in the manner of expression (soccer is a word that lends itself to sarcastic inflection) and not the semantic content.

-

Leading figures and commentators in the

Australian game like Johnny Warren and Les Murray always used the

word ‘football’ when talking about soccer. They did not. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yB0wrU2tWOA (1.43)

Confusion over names is part of the complex history of all

football codes in this country. Australian rules and soccer have

undergone significant name changes in the course of their development,

as have their many organising and controlling bodies – often for

interesting cultural-political reasons.

As the rules of the Melbourne Football Club started their

expansion out of Melbourne into the suburbs and other towns and colonies

(including NZ) the name of the game became Melbourne rules. This

subsequently transformed into Victorian rules and then Australian rules

(with a brief digression into Australasian rules). Today Australian

rules is officially known as Australian Football and also has made

claims on the title of the ‘National Game’.

The game that is initially known in Victoria as

Anglo-Australian football, or British Association rules, or English

Association rules, or (rarely) Scottish Association rules, officially

becomes Soccer football in the 1920s and just plain soccer after that –

though it starts to be described as soccer in the Argus

newspaper from 1908 on. In Queensland, the first organising body was the

Anglo-Queensland Football Association while the game in New South

Wales was initially administered by the Southern British Football

Union. In the Perth press the game is described as Socker for a few brief years around the turn of the century!

This represents a methodological problem for the historian –

if the names of the games and the organising bodies are not consistent

over time or across the various colonies at any given time, we need to

be very careful when we read an historical newspaper article that

refers to football.

For example, an article in a Maitland newspaper in 1883

reviews a match of Association football played by a team named

Northumberland. A present day reader would be forgiven for the immediate

assumption was that it was a soccer team comprised of miners from the

north east of England. Closer reading showed that it was actually a

game of Victorian rules being played by a local team against South

Melbourne FC. In 1894 a game of Association Rules in “was played on the

Albion Ground, West Maitland, under Association rules, between the

Northumberland and Redfern (Sydney) teams. The match was won by the

former by 2 points to nil.”

This match also seems to have been played under Victorian

rules even while the name “Association rules” would have signified

soccer in other parts of Australia.

This changeability of names points to a very different

conception of football from the ones held today – the idea that soccer

and rugby and Australian rules were differing strains of the same game

of football. For much of the first part of the 20th century, newspaper

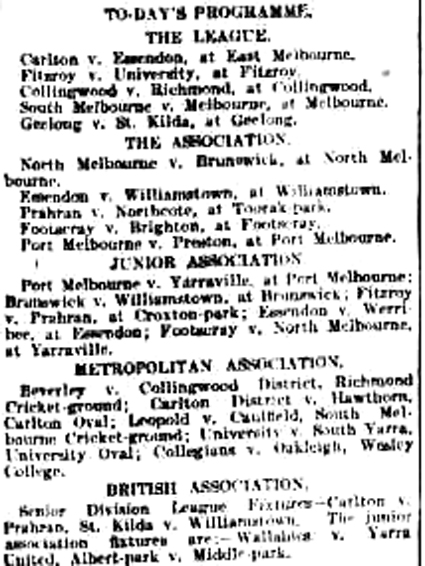

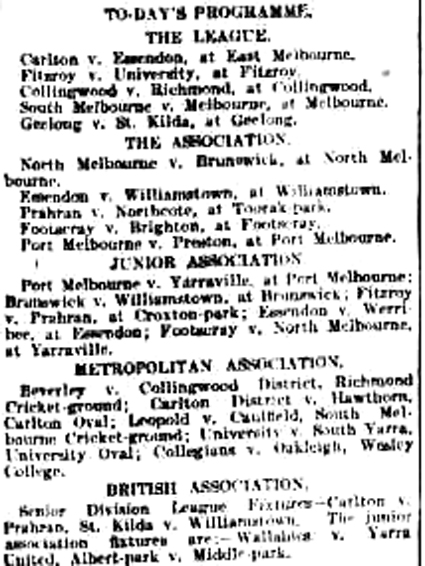

soccer reports were made under the heading of football. Typically, the Argus

would list under the heading of football: VFL, VFA, rugby and soccer.

And while they gave greater weight to Australian rules there was not

the same sense of separation that the media deploys today.

|

| 'Football' match listings, Argus 20 Aug 1910 |

In some papers, the football results were given in such an

order that we can only discern from the actual scores the games that

were being played. And even then sometimes the scores are given

incorrectly. Soccer matches represetented as 6 points to 1 for example.

This too represents a methodological problem. Soccer

reports are often there in newspapers but they are sometimes buried at

the end of or hidden within a general football report. Historians have

overlooked vital pieces of information because of this.

From 1850 onward until about 1870 we get many reports of

football games across Australia where virtually all we know is that

between zero and 3 goals were scored, mostly kicked but occasionally

taken across the line in or by a scrimmage. Many journalists thought

little of posterity when they filed their reports. We know that

different kinds of football were being played but sometimes we have no

idea what kinds.

The FFA’s rebranding of soccer as ‘football’ threatens to

introduce the same kind of lack of clarity for historians of the

future. Therefore I am an advocate for the use of soccer in public

discourse for the time being — at least until history and common sense

determines otherwise.

I will use the terms Australian rules, rugby union, rugby league. When I use the term football I mean it generically.

Football Research

Recent developments in digitised newspaper

archives have forever changed the way history is investigated. Simple

term searches in the

National Library of Australia's digital archive

can now reveal in minutes articles and stories that would previously

have taken months, or even years, of painstaking research to uncover.

One impact has been in the realm of sports history. Sport

cultures based on founding myths and narratives of domination and

permanence are starting to appear more unstable. Sporting history's

white lies and their more pernicious cousins are being exposed. My own

field of research – the history of Australian soccer – is being

drastically reshaped by archival discoveries.

The NLA database is searchable

-- so we can discover evidence that was once nearly impossible to find.

Previously, this data could only be found accidentally or through an

awful lot of hard slog using the old-fashioned techniques of trawling

through microfilm and hard copy newspapers.

Already we can see the potential the database has in disrupting and correcting conventional narratives.

Without having to leave Melbourne, I have made a number of

discoveries in the archive that question some of the established

narratives of sport history in Australia.

Three general examples:

-

From the Hobart Mercury in 1867 we learn of a group of Aboriginal footballers near Hamilton in Victoria.

-

An 1880 regional news report in the Argus records the suppression of a Ladies' Football Club which had been proposed at Sandhurst.

-

The Maitland Mercury reveals a form of football being played in Darwin in 1879.

In each example, factual evidence gleaned from displaced sources troubles established narratives.

Discoveries of this kind have led me to the conclusion that

every narrative, every story is wrong in some way . . . including my

own.

Soccer history

A major suspicion I have confirmed over the past 4 years is

that Soccer has a much deeper and broader Australian history than has

been recorded by sports historians. The game is more ‘embedded' or

domesticated or naturalised than is usually assumed.

The archive reveals that soccer reports are there in

newspapers but they are sometimes buried at the end of, or hidden

within, a general football report, as in the example given earlier. As

is often the case footnotes are particularly revealing.Historians have overlooked vital pieces of information

because of this.

Also many have been guided by master-narratives that

already structure and limit their narrative possibilities. If you read a

local or club history of a Victorian footy club there will usually be a

preliminary section that says something like "football in the region

goes back to the 1850s or 1860s but Victorian rules weren't formalised

here until the early 1860s". Nonetheless the history reclaims that early

football history for footy. What are the other possibilities?

(My own master narrative? Iconoclastic rather than hagiographic)

Consequently I've tried to adopt a sceptical and

open-minded approach. Trust no established narrative; question all

arguments about origins.

Three reasons:

-

Established histories have been compiled with access to only a fraction of the available data and are necessarily limited.

-

There are no origins only moments of confluence. Or, there are no fathers of the game (any game) – though there may be godfathers.

-

Inscription is not origination.

Because something is written down for the first time does not mean that

it is the first time that it happened. The fetishistic emphasis on

written rules and codes (of our own or someone else's) distorts the

historical process.

Discoveries

Trying to find early examples of soccer in Australia, I had

scoured the NLA archive for references to football, soccer, british

association football and had exhausted those searches.

Reading the articles had taught me aspects of the

terminology used at the time and so I was able to make informed

experiments with search terms. Making a search using the term ‘English

association rules' I found reference to a game played between New Town

fc and the Cricketers fc in Hobart on 7 June 1879 .

These clubs met for the return match on Marsh's

ground, New Town, on Saturday afternoon, playing the English Association

Rules. The result was a draw, no goals being kicked by either side.

Yet for many years Australian soccer had had an assumed

origin point. The received narrative was that the first game was played

in 1880 between the Wanderers and the King's School in Sydney. That

game's originary status was undermined by the discovery of the 1879

Hobart game.

Evidence suggests that even earlier games were played.

-

1878 a one-half soccer/one-half rugby game in Sydney

-

1876 the new Petrie Terrace club in Brisbane initially adopts London Association rules

The earliest 'first-game of soccer' I have confirmed

occurred on Saturday 7 August 1875 in Woogaroo (now Goodna) just outside

of Brisbane. The Queenslander of 14 August reported that the

Brisbane Football Club met the inmates and warders of the Woogaroo

Lunatic Asylum on the football field in the grounds of the Asylum:

play commenced at half-past 2, after arranging the rules

and appointing umpires; Mr. Sheehan acting as such for Brisbane, and

Mr. Jaap for Woogaroo. One rule provided that the ball should not be

handled nor carried.

In itself this description is not enough to justify the

claim that the game is soccer (or British Association Football as it was

then known). The clinching evidence comes from the Victorian

publication The Footballer in 1875 which notes in its section

on ‘Football in Queensland' that the “match was played without handling

the ball under any circumstances whatever (Association rules).” (p. 80)

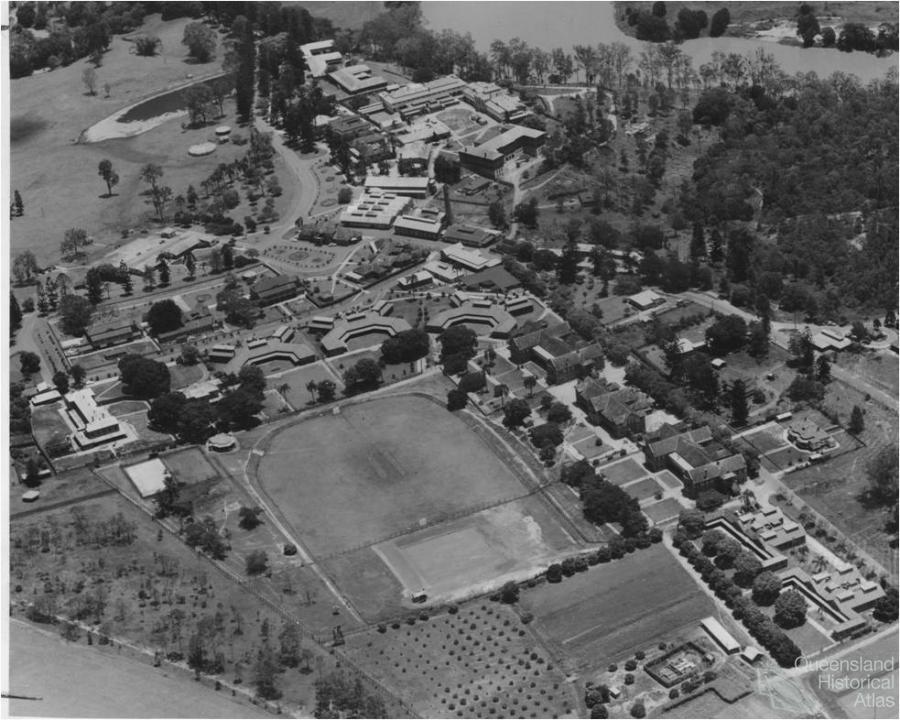

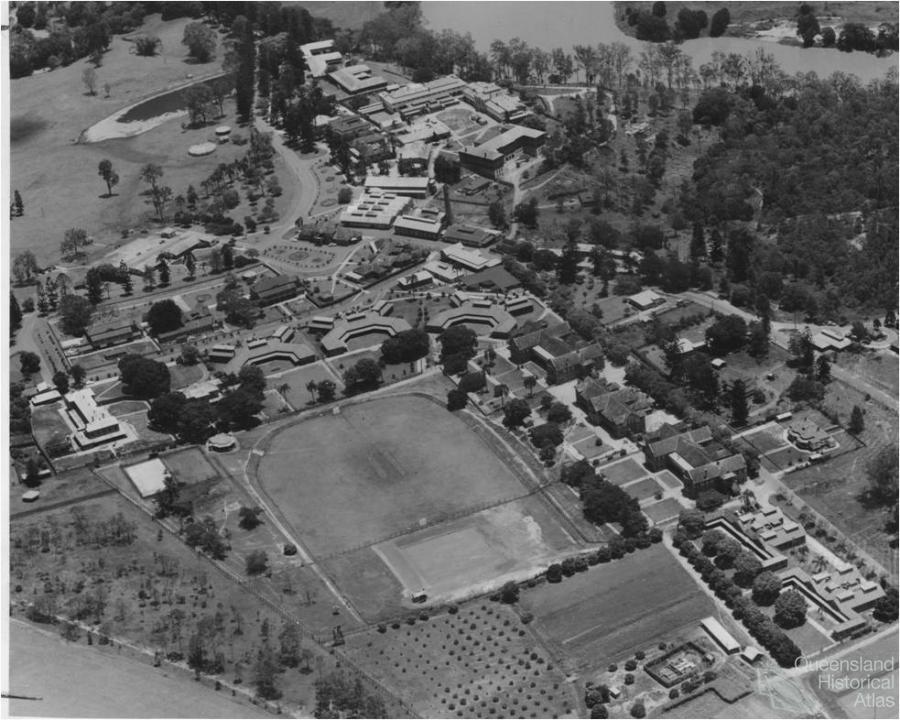

|

Wolston Park Hospital Cricket Ground. Likely site of

the first recorded game of soccer in Australia |

But this is still not the very first game of soccer in

Australia. There is little doubt in my mind that there were earlier

games. A rather tantalising history is suggested by the following list -

all discovered via the NLA database:

-

The

inmates at Woogaroo played an earlier game of football in 1873, and

while the code is not specified it is probable that it was soccer, given

that the superintendent John Jaap was a graduate of Glasgow University.

-

1873 a football association formed in Adelaide which initially adopts English association rules.

-

Throughout the early 1870s we see frequent advocacy of soccer in letters to the editor across the colonies.

-

During the 1870s

games were played in which carrying and handling the ball were

outlawed in a number of places around Australia – Richmond in Tasmania.

Can we describe these games as soccer? If not, how can we describe them?

-

E. 1870s – recollections in the Mercury in the 1920s of soccer being played in the Hobart Domain.

-

It is possible that the 1870 game in Melbourne

between the Melbourne Football Club and the Police was played under

British Association rules – though more research is needed to nail down

this particular game. 1 2

An amusing game of football will be played on the Metropolitan ground, Yarra-park, this afternoon, between the local club and a team chosen from the ranks of the Victorian police force, who will play under the guidance of Mr. J. Conway, of the Carlton Club. The game will be played something after the home style, and holding or running with the ball will not be allowed.

- Letter to Bell's Life in 1867 advocating the adoption of soccer in Sydney.

- A game of Harrow football in Adelaide in 1854 - in which the round ball was not allowed to be touched by hand.

It is my suspicion that as more research is done we will

find many more games of soccer (or soccer-like games) played well back in

Australian history.

A radical challenge to the conventional narrative is

involved in the speculation that when the Melbourne rules of football

were laid down in 1858, 1859 or whenever, soccer was close at hand as an

influence.

Even though soccer was not codified until 1863, games which

had a strong influence on the codification of soccer had been codified

much earlier: Cambridge, Harrow, Sheffield rules. And they had been

brought to Melbourne in informal ways.

My article in Meanjin.

Indeed ‘a game resembling soccer' is a way to describe

the very first example of the Melbourne Rules laid down in 1859, as

‘Free Kick' attests:

The [English] Football Association was accordingly

formed, and set of rules drawn up, which by a very curious coincidence,

are very nearly similar to those which were decided on at a meeting of

representatives of football clubs, held at the Parade Hotel, near

Melbourne, some 5 years ago … Whether a stray copy (for the rules were

neatly printed and got up) ever found its way home I do not know, but if

not it is a strong argument in favour of our own code, that the

football parliaments assembled on opposite sides of the globe, should

bring the identical same result of their labours.

(‘Free Kick', letter to Bell's Life in Victoria, 14 May 1864, p. 2.)

As far as ‘Free Kick' is concerned, the similarities

between soccer and Australian football in 1864 were far more significant

than the differences. Indeed, games resembling soccer have been played

in Australia for as long as any other code of football.

There we have it: soccer was in the vicinity at the

beginning of organised football in Australia. It has been a part of the

sporting fabric of the whole nation ever since. And it remains a

significant part of our sporting landscape. Its ongoing struggle for

legitimacy then is surely an object of bafflement.

Soccer's struggle for legitimacy

Organised soccer is at least 140 years old in Australia.

500,000 Australians are registered soccer players, higher participation

levels than any other team sport. The ABS estimates another 800,000

playing at less formal levels. At its elite level, soccer is capable of

generating massive television viewing statistics. A Socceroo game at

the World Cup, for example, is arguably the high-water mark in

Australian sports viewing (even in the middle of the night), surpassing

the AFL and NRL Grand Finals and the Melbourne Cup. While soccer tends

to be the second football code wherever it is played, it nonetheless

has the kind of demographic Australian coverage that the other football

codes would envy. Soccer’s numerical strengths (and some of it

cultural weaknesses) are indicated by its status as the ‘go to’ game

for Australia-wide advertising narratives that represent children at

energetic play.

http://www.youtube.com/embed/ivxP-UujQak

The ad appeals to kids and parents across all Australia in a

way that Australian rules or Rugby League could not. Yet it also

invokes the idea of the soccer mum and the 'weaknesses' that notion

implies.

Yet this game, even with such an apparent comparative

advantage, has fared badly in Australia. Since 1880, organised soccer

has sought a place in Australian society only to be rebuffed and

rejected as a foreign game, a threat, sometimes even a menace to

Australian masculinity and life in general. The game has endured

sustained media myopia offset by frequent outbursts of intense and

spiteful attention. Johnny Warren encapsulated this anti-soccer

mentality in the title of his memoir,

Sheilas, Wogs and Poofters.

These were the kinds of people who played soccer in

Australia (though Warren might have added Poms and Children). The game

was seen as effeminate, foreign and for men of what was constructed as a

degenerate sexuality. While Warren’s title doesn’t quite represent

either the totality or the subtlety of opposition, it does capture the

vituperation and the spirit of a different age. He relates the story

of a tickertape parade for the Australian national team (the Socceroos)

in Sydney in 1969.

I have a daunting image, still prominent in my memory.

It was the occasion of a ticket tape parade for the Australian national

team in 1969. I had taken my allocated place in one of the sports cars

which had been organised for the event. The cavalcade was snaking its

way through the streets and turned a corner. This one particular corner,

like so many of its kind in Sydney, was adorned by a pub. Wooing the

punters to drink from its kegs were pictures on its outer wall of

rugby, cricket and horse racing. True-blue Aussie sports. Spilling out

of the pub’s doors were tank-topped, steel-cap-booted, tattooed workers

quenching their thirst after the dust of the day’s work. ‘Fuckin’

poofters,’ some hooted at us. ‘Dago bastards,’ followed others. The odd

projectile was hurled our way. Needless to say, I had, in my life,

felt much safer than I did during that parade. (ppxxi-xxii)

The recent relative successes of soccer in Australia

might tend to suggest that the bigoted attitude that confronted Warren

is a thing of the past. The way that the A League and well-attended

internationals have elbowed themselves some room in the mainstream of

Australian sport media indicates a new-found respect for the game has

been established in Australia. However, the battle may not be over.

Recent case of Moonee Valley Footy Club suggests that the fear of a soccer invasion is still present in some minds.

Even when this vulgar and coarse resentment (usually

designed to sell newspapers) is peeled away a core of repulsion,

sometimes principled, more often irrational remains.

The former comes from a writer like Martin Flanagan who

believes that any weakening of Australian rules football because of

soccer’s rise will damage our local culture, already embattled by the

manifold forces of globalisation. Flanagan respects soccer and other

codes of football but he makes his priorities clear. He believes that

Australian rules

has a unique place, not only in Australian sport, but

in Australian culture which, in my experience, is obvious to outsiders.

I can admire the Australian rugby union team and enjoy watching them

play, but at the end of the day it is a British game they’re playing.

Australian football is a marvellous sporting invention that found its

way into the hearts of people and infiltrated other aspects of their

lives so that it became something by which you knew families and

suburbs and towns and, more recently with the national competition,

different parts of Australia.

While this argument is one that deserves notice, largely

because it is true for much of Australia, it is flawed when we look at

Sydney and broad regions of the northern states. The problem is that

Australian rules is an irrelevance for many Australians, even many of

those who are interested in sport. They do not play it; they do not

watch it; they fail to understand it. Nor have they experienced the

purported social benefits of the game to which Flanagan refers.

Significantly, in one of the heartlands of Australian mythology, what

might be called the Waltzing Matilda country of outback Queensland,

Australian rules is an utterly foreign game.

Flanagan does not allow for the fact that the so-called

‘British games’ (the Rugby codes and soccer) have also given and

continue to give meaning and structure to the lives of many Australians.

And unless he is willing to say that these experiences are inferior to

or less authentic than the social meaning obtained through Australian

rules, or that these Australians aren’t true Australians, then

Flanagan is guilty of making a national generalisation out of a

regional truth. In many regions and towns soccer has a continuous

history of more than 100 years where the game has been, for generations

of Australians and waves of migrants, an important pillar of their

communities. In Flanagan’s home state of Tasmania, the South Hobart

Football Club has a 100 year history and has played at the same ground

for most of that time. The club is embedded in the community in ways

that Flanagan would admire in relation to an Australian rules club.

Representing a very different perspective is a writer like

Michael Duffy, whose article, ‘Jig is up - give World Cup the boot’

published shortly after the 2006 World Cup, is a checklist of

predictable prejudice that masks his own failure to understand the

game: boring; not enough scoring; should be allowed to use hands; too

much play acting. He talks about an experience of watching the World

Cup that, given his attitudes and the second-person persona adopted, is

probably second hand or made up.

You rose from your bed in the early hours to spend an

hour and a half watching the ball move from one player to another

several hundred times without passing through the white posts at either

end of the field more than once or twice. It was like golf without the

excitement.

If Flanagan adopts a left-nationalist position in worrying

about soccer’s globalising effects, Duffy comes from the free-market

right and argues the very opposite. Inspired by the American academic

economist Allen Sanderson, Duffy suggests that Australians are very

much like Americans and we should see their resistance to soccer as

exemplary. He cites Sanderson who believes that those Americans who

support soccer “are uncomfortable with competitions that produce

winners and losers, and soccer appeals to their egalitarian,

risk-averse streak. The same crowd usually also can be counted on to

oppose globalisation.”

Duffy also sees soccer is also a force of political

correctness: “Lots of parents force their children to play football for

reasons of social engineering: they want to make their boys more like

girls and their girls more like boys.” For Duffy men’s sport is about

upper body strength. As a sport that disallows the use of hands, soccer

therefore runs against the spirit of unfettered competition that

characterises the true sporting contest. Anyone who has seen

Michael Duffy will note a quaint irony in his being critical of

anyone’s upper body proportions. Indeed, Duffy continues the great

right wing tradition of puny old men urging on strong young men to do

their dirty martial work for them.

Despite their having completely antagonistic perspectives

on virtually all other cultural-political matters, Flanagan and Duffy

end up on the same side in this argument. This speaks greatly of the

general antagonism to soccer in Australia, particularly from middle-aged

men (with Irish surnames) with positions of some cultural influence.

But Duffy and Flanagan did not invent their perspectives.

They inherited them. Their pronouncements on soccer have a genealogy

that extends back to before soccer was even codified in 1863. And there

are very good reasons for the resentment of soccer. The game’s

reputation has legitimately suffered through fan violence and farcical

organisational corruption around the world. Throughout history it has

been variously held responsible for the collapses of moral order and

collective political will. It has been a game of the economic colonizer,

imposing itself on or being taken up by indigenous people who have

thereby lost contact with their native customs. In ancient times its

forebear (folk football, which is arguably an important precursor of

all football codes) was even outlawed by monarchs afraid of the game’s

impact on their fighting forces.

But none of these relates directly to the main source of

contemporary vilification, which might be called ‘soccerphobia’.

Soccerphobia is the fear of one particular code of football,

Association football and its supposed potential to damage national,

regional and local cultures. The loudest bastions of soccerphobia are,

curiously, found in Anglophone countries with a long and direct colonial

connection to the British Isles – the birthplace of Association

football. Australia, the United States of America, Canada, Ireland, New

Zealand and South Africa all house strong and entrenched cultures of

soccerphobia. In three and one-half of these countries, soccer is seen

either as a threat to local and established games or as a game that

cannot assimilate because of its foreignness or unsuitability.

Ireland, Canada, the USA and southern and western

Australia have developed regional variations of football (or other

sports) that are assumed to be indigenous expressions of nationality –

assumptions that are often flawed. For example baseball’s claims to

indigenous status ignore the obvious fact that it stems directly from

games imported from Europe. Often, claims of indigeneity rest more on

politically expedient assertions of national independence than they do

on historical fact.

In New Zealand, white South Africa and the Australian

states of Queensland and New South Wales the local/imported divide is

not as relevant – or at least it has little basis to be. The dominant

football codes (Rugby Union or Rugby League) in each of these states or

countries have clear British origins. Here, the disparagement of

soccer tends to focus on questions of courage, masculinity and even

sexuality. Historically, Association football has been seen as a game

for degenerates and weaklings across the soccerphobic world.

In recent times, the idea of sport-as-industry has been

clarified. While organised elite sport for the past 120 years or more,

has had the element of profit-and-loss at its heart, for much of that

history the ruling mythology of sport provided a smokescreen, placing

the economic realm into the category of a ‘necessary evil’.

Contemporary sports discourse happily brings questions of economics to

bear. This newer general consciousness of sport as business is one

which perceives any attempt to grow a sporting market necessarily

involves a diminution of another and competition between sports becomes

a legitimate subject matter for sports discussion. Soccer’s attempts

to gain ‘market share’ in those regions where historically it has been

less dominant are one more basis for soccerphobia, a position which can

dip into the toolbox of cultural soccerphobia as required.

To leave it at this would be to allow soccer to cry

victim without accepting a deal of responsibility. Soccer sometimes has

only itself to blame. While the game has risen and fallen subject to

external pressures, it has, in perhaps equal measure, been

self-sabotaged by its internecine feuds and unfathomable incompetences.

One could also point to historical factors. Soccer has

regularly collapsed under the massive weight of war and Depression and

often resurged on migrant tides. And while history has not been kind to

the game in Australia, it might be said: “In sport you make your own

history!” In a sense soccer has not been kind to its own history. It has

not often made a good fist of becoming a narrative point of Australian

history. Nor has it done a very good job of remembering the times when

it actually did.

The game that never happened

This is the problem around which my research

turns: Australian soccer has failed to rise to the level of mythology,

legend and story in Australia. Philip Mosely and Bill Murray put it

another way: “it has not entered the Australian soul”. Roy Hay claims

that “there has been a failure to make the game Australian.” It has not

managed to insert itself positively into the narratives that

Australians tell themselves about themselves. This is the basis upon

which it is possible to utter an apparent falsity – that Australian

soccer is the game that never happened.

Even though there continue to be countless moments of

individuals, teams and organisations seeming to play and organise

soccer matches and competitions, the game has never

really happened in and for itself. A mythology has arisen in which soccer has been an

instead game and a

nearly

game, a counter-attraction or curtain-raiser to the main game wherever

and whenever it has been played. Australians have played and watched

soccer as a digression, a replacement, a substitute, a surrogate, a

next-best thing at best, when they would rather be doing something

else, somewhere else.

The construction of the Anzac legend is pertinent here.

So games of soccer that were very much played, and won

(or drawn) did not ‘happen’ in the sense that they did not register as

having happened as significant moments of

Australian behaviour.

Like mirages, they appeared on the horizon and vanished as suddenly as

they emerged not even to be consigned to the scrapheap of history but

almost to disappear, leaving little but unsettling personal memories

and a thin archival trace.

Australian soccer is a game on the edge, literally and

metaphorically. It is a foreign game and has remained so for all of the

140 years or more that Australians have been playing it in an organised

fashion. The earliest direct ref to its foreigness in 1905 though its

Britishness was usually emphasised in earlier reports. Indeed, it is

sometimes a “wicked foreign game” that menaces and threatens to overrun

Australian society, steal our land and brainwash and enfeeble our

children. Its values and practices are ‘other’ and the game has

periodically been asked to go back to where it came from.

When it does find a temporary residence here it is often

on the edge of the comfort zones of our suburbs and towns, on grounds

built on industrial wastelands and recently reclaimed rubbish tips.

(Somers St) Australian soccer has had to fight and scrap against more

permanent and established residents for every piece of land to which it

has access. Only rarely has such land become a settled home for the

game. Freud might have described the condition of Australian soccer as

unheimlich, in acknowledgement of its homeless and uncanny presence in Australian sporting culture.

Australian soccer is a game on the edge of attention,

often languishing in the shadows cast by bigger edifices, silenced by

the white noise of mainstream sports trivia. Mainstream media outlets

down the years have rarely supplied good coverage of the game (peak

moments aside), usually relying on the nincompoopism of the circular

argument: “We don’t cover it because there is little interest.

Australians don’t follow soccer,” thereby simultaneously confessing and

justifying their failure to lead or create that interest or follow

whatever interest that does exist.

The 50,000 Victorian players receive no mention on a weekly basis in either of the main Melbourne newspapers.

Newspaper and other media audiences have been reminded and

reminded for the past 150 years about how little they know about this

‘brand-new’ game, soccer, leaving those who consider they

do know the game feeling like uninvited guests.

Soccer sits on the edge of history in Australia. It is

never a core theme for the historian – though perhaps sometimes an

interesting sideline (or Greek chorus!) to the main story. Historians

refer habitually to its novelty, difference and foreignness. Sporting

histories are little better. While able to respect the game as a

legitimate object of research, they are still written under the sway of

the myths of soccer’s marginality. Sport historians find it harder to

see soccer as a

subject of research. Even those histories that

profess to tell the story of the game from the inside can be diverted

by the all-pervading mythologies that have built up around sport and

culture in Australia. They are liable to take on board non-negotiable

truths that rule the game out of the game.

Soccer is a game that arrives in Australia; other sports tend to rise or emerge.

Many soccer historians have been complicit in their own

marginalisation, happy to provide comments from the sideline rather

than fight their way into the commentary box.

Australian soccer is on the edge of Australia – again in

two senses. It is only played around the edges, in the big cities, home

to the migrants, that leaf-fringed demense despised by the architects

of bush nationalism. AD Hope’s ‘Australia’ has this biting stanza:

And her five cities, like five teeming sores,

Each drains her: a vast parasite robber-state

Where second-hand Europeans pullulate

Timidly on the edge of alien shores.

While not about soccer, Hope’s poem is about

its place, the “second-hand Europeans” who live there and that place’s

relation to the spiritual centre of Australia. The rugged heart, the

heroic source of

real Australia is not a place of soccer.

Yet when we look closely, soccer in rural Australia - even

in rural Victoria - goes back a long way. Mildura 1890s, Gippsland 1910s. Horsham had a competition in the 1920s.

Warwick in Qld 1912.

Australian literature, legends and mythologies are

constructed as soccer-free narratives and the game’s intrusion in them

is rare and ever dissonant when it does occur. Australian soccer has no

Cazaly up there with whom its players can go – whether that be to

popular adulation or to their deaths in the field of battle. It has no

“six-foot recruit from Eaglehawk” to provide its “hope of salvation.”

There are many Australian soccer players who have “come down from the

bush” but the game has access to no mythological narratives in which to

accommodate them. The game might be able to boast Kasey Wehrman, an

Aboriginal hard man from Cloncurry, but it cannot point to any

archetypal bush heroes in its pantheon of greasy wogs and sneaky

Scotsmen alongside whom he can sit.

Nor does Wehrman have any tangible Indigenous notables to

provide fatherly mentoring. The deeds of Bondi Neal, Charles Perkins,

Gordon Briscoe, John Moriarty and Harry Williams could shine down the

ages as beacons to young Aboriginal players because they were genuine

stars of Australian soccer, a game to which Aboriginal players were

welcomed in ways other codes of football found difficult. Yet this

moment, like many others, has vanished from public perception and

Aboriginal players are largely absent in the stories of Australian

soccer.

Ultimately Australian soccer is a game on the edge of

legitimacy, a game at the edge of itself. And while we inhabit a

cultural conversation that can accommodate the perversion of logic and

sense that allows the nation’s most played team game to be figured as

un-Australian and marginal it will be ever thus.